Photo Illustrations MURP 5145

Engineering and Planning: Are we learning to make better places?

History of Olivier Plantation House: http://www.richcampanella.com/assets/pdf/article_Campanella_Preservation-in-Print_2017_Dec_Olivier%20House.pdf

Proposed future of this plot: https://www.nola.com/news/article_393949ab-d2fb-5ace-a324-1cd125578540.html

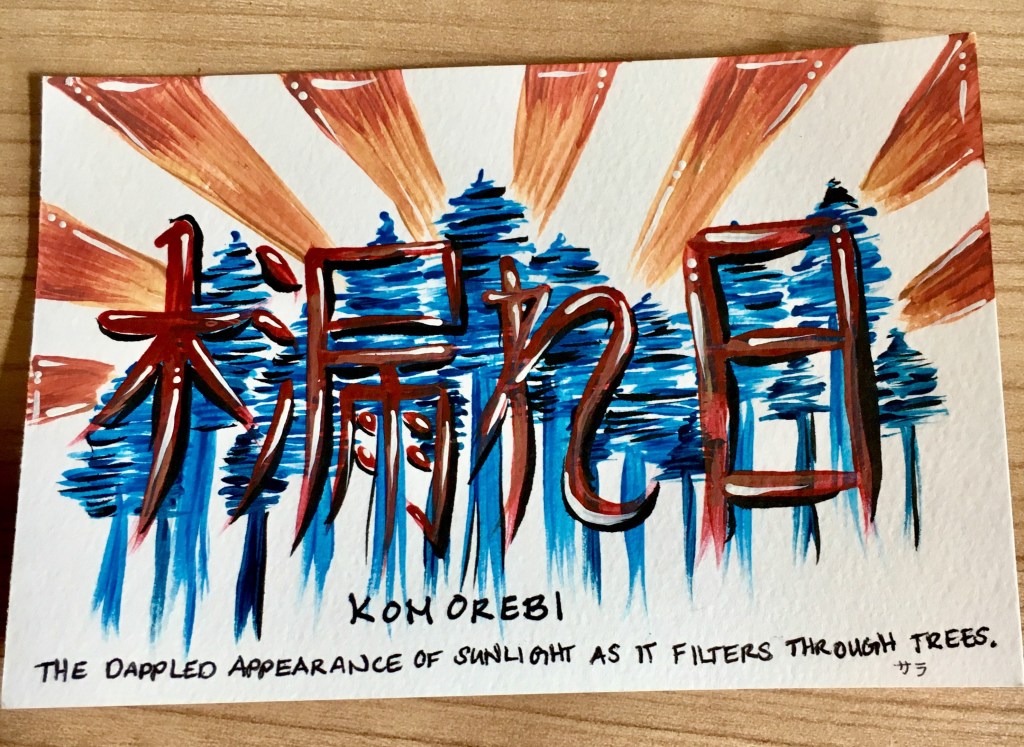

art from Japan by Sarah Schafer

This photography collection is my addition to our shared work on the Gulf coast. As a whole, the photos are not just of things, but of social relations mediated through things -primarily water.

On Isle de Jean Charles, there were once over 700 families. As of July 2019 there are less than 20.

Residents can move, but their way of life is nonetheless coastal; an antagonism persists. In this new lived experience, the coast is itself, mobile. Coastal culture in this collection feels at times incongruous and incomplete -as starkly juxtaposed against its surroundings as dead coastal trees against a large Louisiana sky. Yet it also still feels completely experienced.

The picture with the off-shore submersable leaves a lasting impression. There was a film done on this barrier island and it seems that even the film leaves remnants. Like a padlock on a bridge. Perhaps a placemaking tool, perhaps heavy garbage. There is a clause in the buyout contract for residents of Isle de Jean Charles that that says you can no longer upgrade your house. If residents accept the buyout, they sign two mortgages. One for their new free home in a new subdivision, and one for the home on the island which allows them access to that land, but prevents improvements on their home. The goal of the buyout is to move residents; to depopulate unstable land. The contractual language of the process of coastal landloss is echoed and drawn out in the photos from the island to articulate the odd dissonance that someone else buying land there without such a mortgage is subsequently not subject to the restrictions because they do not sign a contract with the United States government. You can be of Isle de Jean Charles but paradoxically and ruthlessly, it is going to be very difficult to be from Isle de Jean Charles.

The cement statues that are the Chauvin sculpture garden built by artist Kenny Hill, is a set of photos that recognize an authentic coastal relationship, one that intervenes and cuts across the photography.

What will these statues look like when these are underwater?

The fishermen in the boat, taken on Isle de Jean Charles tells a story that there is no way to fully recognize. The beauty in this picture, if there is any, is in the relief that it rests in the shadow of. The catch is redfish and speckled trout. We had just heard a story of how on Lorianne’s mothers side of the family, 8 out of 10 kids died of cancer. The remaining two are each two-time cancer survivors. There is no way to even recognize what is being done to the processes which constitute our ways of life. There are relationships which are being served in this approach to photography.

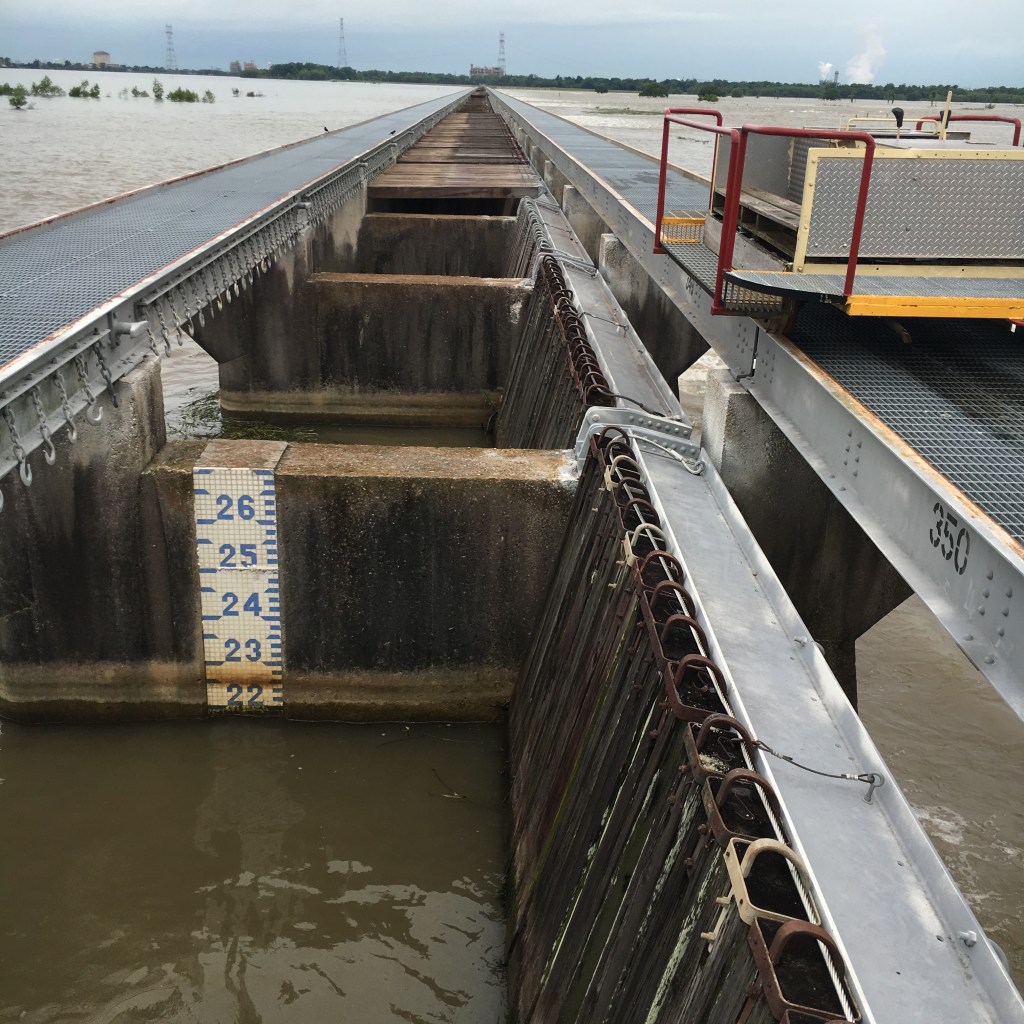

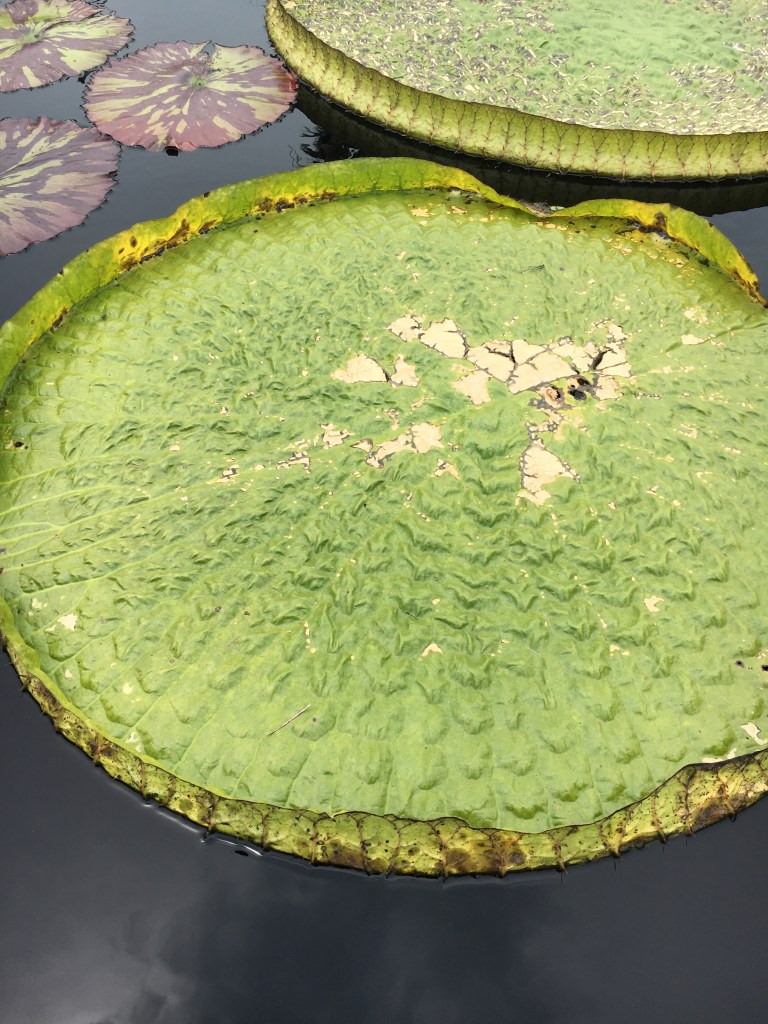

water is the theme of this body of work. The relationships between water and people and places are relationships which on occasion, are seen through a static image.

Dangerous and beautiful, water inspires artwork and city parks; it also changes what it is like to live our lives. To make ourselves fit with water. There is an example whereby a glass is filled with water, and then a stick is set in the glass. The stick looks bent. The stick, if you remove it, is as it was, but when replaced it is confirmed, the stick looks bent.

we would love to swim but there are no places to swim. Where would we go? The Mississippi river, or Lake Ponchartrain?

we would love to fish, but we need a car or a boat, a license and a public spot.

Anyhow, the stories of the Gulf seafood in the wake of the BP oil spill -the ongoing refusal to address the oil and gas complex, make seafood’s sourcing come sharply into focus.

We are surrounded by water yet its relationship is not what it might appear.

It is so beautiful to have Crescent Park, yet the park is clearly one of the best locations for catching river barges that run into land. The pictures of where the public cannot go are questions of the relationships between a park and the public. We can see the cranes and the active development of downtown New Orleans real estate, but there seem to be more and more places that explicitly inform others where we cannot go.

This semesters photos were collected into a selection of 50 images as arrangements of coastal relationships. Working with New Orleans artist Danielle Hein, the collection was arranged to highight small details of the photography and from these magnified details, an opportunity to see the universal features in abstraction. The metaphor of where we are today, is ideology. These images are source images; to go to the source is not to get answers, but rather, to learn ongoing struggles which constitute the all-important, life of the coast.

The inconsistent, fractured, and gap of this work is not overtly pessimistic, but it is a difficult pallate to get adjusted to. In summary, we cannot say simply, “let the people speak! We must open ourselves to the people!” This is more refined but a no less-dangerous form of populism. We need not elevate the man waiting for the bus behind the flooded bus stop into some kind of ordinary source of wisdom that we corrupted academics are not able to get at. As this body of work will affirm, we understand anxieties and feelings and context, but we will not get any deep message of what to do. We have to reinvent the way ahead. ‘Let’s ask the people’ does not do the job.

The photography in this selection is composed and edited at the instruction of Heater’s basic composition guidelines. The balance and framing of the body of work improves notably as the semester progresses as does the quality of the work. Distinct coastal locations and critical elements that make place unique are foundations of urban planning, hazard mitigation, and coastal restoration discussions more broadly. The photographs in this work are aspects of the coast insofar as they are at once the result and driver of coastal activities and coastal identity.